Cannibal

Hurley Winkler

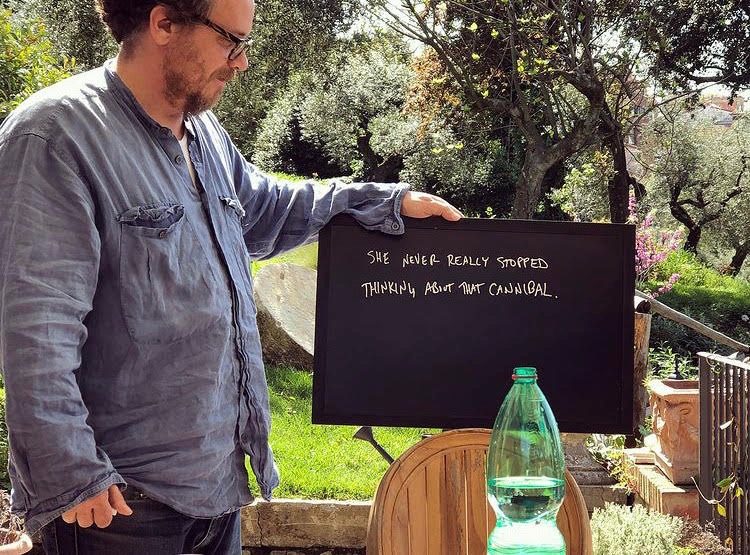

One evening in Italy, Giancarlo and Chelsea asked us to bring a strong sentence to the table the next day. I toiled over mine that night—in my notebook, I wrote (and crossed out) several potential lines:

She couldn’t seem to stop thinking about that cannibal.

She couldn’t bring herself to stop thinking about that cannibal.

Try as she may, she simply can’t stop thinking about that cannibal.

The next morning, Chelsea started class by saying, “Let’s have Hurley go first.” I handed the sentence I’d narrowed down to Gian, who copied it on his chalkboard—She never really stopped thinking about that cannibal.

As he copied it down, he grinned, then said, “That’s pretty good.” Then, he got to work, hovering his chalk above “really,” about to mark it off. But after a moment, he pulled the chalk away and said, “No, the ‘really’ needs to stay.” Then, he went for the “that,” but did the same thing: “‘That’ does, too.” He nodded, told me I did a good job, and in the same breath asked, “Who’s next?”

At least one sentence in the following story has Gian’s stamp of approval. As for the rest, I can only hope he’d like them.

+

She never really stopped thinking about that cannibal. Same way her friends all seemed to hear a chorus in their heads chanting, Nicotine. Nicotine. She’d never smoked, but she knew that chorus well, the way it sang three syllables at a time: Cannibal. Cannibal.

Four women’s bodies discarded in the river, thighs sliced off. The journalists all wrote around the victims’ builds with words like “full-bodied,” like they were aged Barolo.

At parties, she’d catch herself talking about him. “Can you believe they haven’t caught him?” she’d ask her friends, who replied with troubled stares. She once looked at a date like that when he said he hated whales. Claimed they took up too much space. Same way she always felt about herself.

Back when her friends still invited her outside for smoke breaks, they’d present their packs to her, a cigarette partially withdrawn. She never took one, though. Not even after her mother claimed that cigarettes could help make her thin. She knew that wasn’t true—none of her friends were exactly her goal weight. And besides, smoking would only slow her down at the gym. She’d raise the speed on the treadmill anytime she heard that word—cannibal, cannibal—purged from news anchors’ mouths.

If he’d seen her at the hardware store earlier today, what would he have done? When she reached for a box of lightbulbs, she imagined him smashing one against the display. Top shattered, he’d use the rest as a fork and dig into her—right thigh first, then the left, just as the medical examiner had described. Winding through aisles toward the register, the bulbs rattled in her hands.

It wasn’t until she twirled one into her nightstand lamp that she realized she’d bought those LED bulbs by accident. “Blue light,” they call it, always pinning it against terms like “REM cycle.” Not that she really slept anymore. If her mother ever saw her bedroom in that light, she’d have a fit. Even the sheets looked worse—the little messes of her she couldn’t catch in time, blotches of rust and cornsilk, were more apparent. Stains only a cannibal would want to see. Had her mother been there at the store, she would’ve reminded her, “Soft white.”

She clicked off her bedside lamp and meandered right back to him. Even with lightbulbs and sheets and her mother in the foreground, he was always there, lurking famished in her mind’s stairwells.

“Surely you aren’t still thinking about him,” her mother would say. “Are you?” Then, she’d spread out a thick platitude, something like, “Be careful what you focus on. When you focus on something, it expands.”

Just what that cannibal probably wanted—to expand. Same way she’d done before she lost all that weight. Lying in bed, she felt along the stretch marks on the insides of her thighs, proud that they’d gotten as deep as the scratches on her apartment’s floors. She traced her own topography on that cannibal’s behalf. Fantasized about him passing her up. Skin and bones, she assured herself. Bones and bones. Hardly anything to bite into.

From her nightstand, her phone illuminated the room. News alert—they got him. A man in custody, nose crooked in his mugshot like someone had kicked it. She barely breathed as she scrolled through the coverage, picking every crumb of it off the plate. The excuse that had become her pulse—he won’t get me if I’m thin; he won’t get me—drained out of her.

So why was she pulling at her thighs now, noticing how much there still was for her to pinch? She didn’t have to keep shedding herself like this. A healthy person wouldn’t. A healthy person would hear their own bellowing stomach and obey it. So she shoved on her coat and willed herself toward the 7-Eleven chip aisle. Funyuns—her old reliable snack. Yeah. Fun.

She peeled the bag open outside the store, and as she pushed one reluctant Funyun to her lips, she noticed a man pumping gas. Watching her. Nose, crooked. An awful lot like that cannibal’s.

That old chorus started up again. Cannibal. Cannibal. She watched his eyes steer down her body. Wondered if he liked what he saw. If, despite her best efforts, she was “full-bodied” enough for him. She lowered the Funyun—she wasn’t about to let one impulsive snack give him the wrong idea.

The side of his gas pump, she noticed, was covered in Newport pleasure! What if her mother had been right about smoking? She imagined one puff burning away her body the way bonfires shrank newsprint, funnies and all. That chorus in her head started singing a second tune. Nicotine. Nicotine.

She slammed the chip bag in the trashcan and rushed back inside for a pack and a Bic. But when she finished at the register, that crooked-nosed man was heading inside.

If he were to withdraw a knife, aim for her thighs, what would she do? She’d tap out one cigarette, and before taking her first puff, she’d say, “Sir, let me handle this. I can carve myself away all on my own.”